III. CORRUPTED DEMAND

On the topic of The International Degeneracy

Corrupted Demand: QE and the Degeneration of the West

The genesis of Western “International Degeneracy” lies in QE, pioneered by the Bank of Japan in 2001 and adopted globally post-2008. By flooding markets with liquidity, central banks triggered the Cantillon Effect: a regressive transfer of purchasing power to financial institutions at the expense of wage earners. We can model the interaction between growth (G), corruption (C), and unemployment (U) as:

Where β is the “attack rate” at which distorted financial flows divert resources into unproductive “zombie firms”—companies that survive only through suppressed interest coverage ratios (ICR < 1 for 3+ years).

Bitcoin: The Reality Anchor vs. The Tulip Myth

While critics liken Bitcoin to the 1637 Dutch Tulip Mania, empirical data shows a fundamental divergence. Tulips were a 3-year local fad; Bitcoin is a 17-year global asset. [6] Its value follows Metcalfe’s Law, where fundamental value (V) is a function of network nodes (n):

Bitcoin serves to “discipline” monetary policy by providing an alternative currency that cannot be printed to hide structural decline. Its creation message, “Chancellor on brink of second bailout,” tethers it to the peak of the 2008 financial instability. [7]

Loading embed…

View on XGeneration Z and the Reverse Flynn Effect

The most visible “degeneration” is the cognitive decline in Gen Z, who reached maturity during the peak QE era. For the first time since records began, a generation is scoring lower than its parents in IQ and problem-solving—a reversal of the long-running Flynn Effect.

Loading embed…

View on XTable 2: The Divergence in Gen Z Performance (2008–2023)

| Metric | Point Change | Economic Context |

|---|---|---|

| SAT Math Rigor | -71 | Softening curricula / grade inflation |

| Student Math Performance | -36 | Digital multitasking / screen saturation |

| Total SAT Divergence | -107 | Total loss in mathematical proficiency |

| FICO Credit Scores | -3 | Student loan delinquency / debt-stress |

This stagnation is linked to “financialization.” With 52% of Gen Z unable to afford basic costs despite record stock markets, the incentive for deep human capital accumulation has been replaced by short-term digital engagement and “finfluencer” herding behavior.

On The Problem of Corrupted Demand

Hedonist-driven demand is "Corrupted Demand." It is demand for comfort, not capacity. This creates a fundamental problem: if we allow unlimited consumption of trivialities, we risk starving the Architect (Scientist/Engineer) of the resources needed for civilizational advancement.

The question becomes: How do we prevent the Hedonist from consuming the entire energy budget on VR simulations while the Architect tries to launch rockets?

I. The Economic Consequence of Corrupted Demand

In a money economy, the Hedonist bids up the price of trivialities (status goods), sucking resources away from the Architect. Money is value-neutral. It thinks a $100 pair of digital sneakers is "worth" the same as $100 of Fusion Research.

- Money: "Both generated $100 of GDP. They are equal."

- Physics: "False."

- The Sneakers consumed low-entropy energy and turned it into high-entropy waste (status signaling). Net Negative.

- The Fusion Research consumed energy to create a mechanism for infinite future energy. Net Positive.

The Distortion: In a money economy, the Hedonist bids up the price of trivialities (status goods), sucking resources away from the Architect. In an Exergy economy, the "Entropy Tax" punishes the waste. It makes the digital sneakers "expensive" (in terms of social credit) because they waste energy without building capacity.

II. The Entropy Tax: The Mathematical Guardrail

To prevent the feared “Corrupted Demand” (endless digital distractions at the expense of space), the framework introduces a policy variable: The Entropy Tax (τe).

We define 'Corrupted Demand' as energy spent on Low-Entropy Reversal (trivialities) vs. High-Entropy Reversal (civilizational survival).

Consider this:

The Mechanism:

The Hedonist pays a surcharge on their massive energy consumption (the "VR Tax"). That surcharge directly subsidizes the "CapEx" of the Architect's fusion plants and rockets.

Which means:

That surcharge directly subsidizes the "CapEx" of the Architect's fusion plants and rockets.

Which Results in:

The Hedonist's "corrupted" desire for a massive energy grid inadvertently funds the infrastructure that the Architect uses to leave the planet.

III. The Entropy Surcharge in Practice

We cannot allow the Hedonist to burn the entire planetary energy budget on VR simulations while the Architect tries to launch rockets.

The Mechanism: A progressive tax on Energy Intensity.

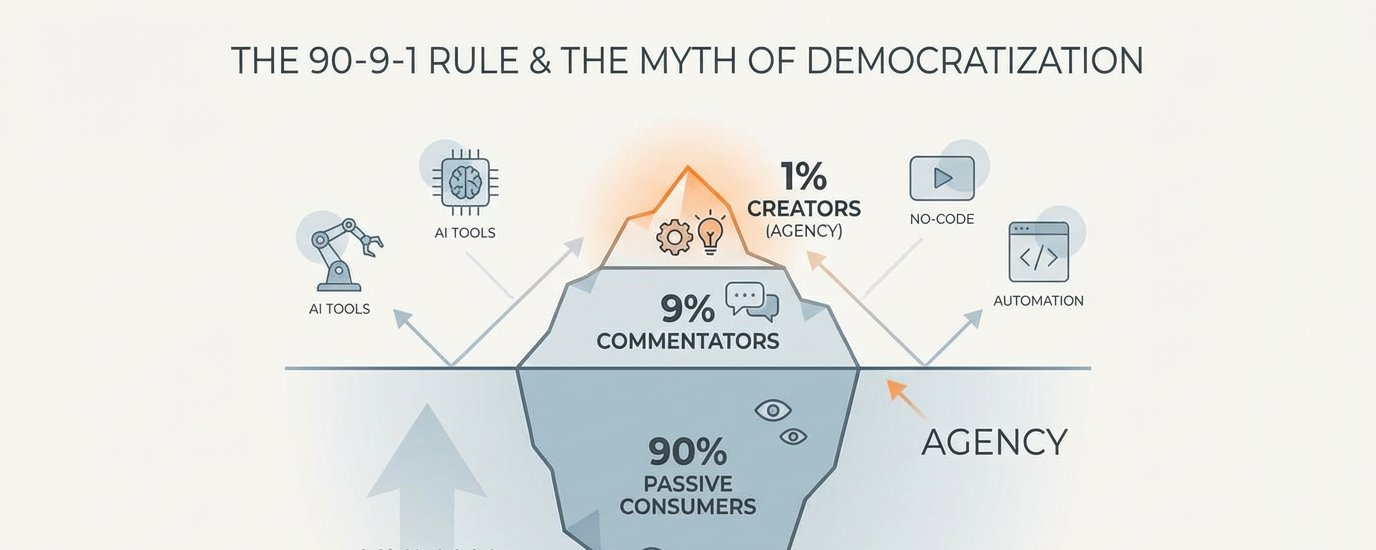

Source: @brivael (X). Why it matters: The 90-9-1 rule frames how Ascetics are defined in the Entropy Tax / tiered-consumption framework—most use little (survival tier), few consume heavily (hedonic tier).

- Tier A (Survival): Basic residential power (Ascetic level) = 0% Tax.

- Tier B (Productive): Industrial power for manufacturing/farming = Low Tax.

- Tier C (Hedonic): High-entropy consumer burns (luxury travel, massive personal compute, decorative energy) = Exponential Surcharge.

The Outcome: The Hedonist pays a premium for their lifestyle. That premium directly subsidizes the "CapEx" of the fusion grids and spaceports. The Hedonist funds the Architect.

IV. Caveats and Considerations

The objection that “who decides what is trivial?” is real—labeling consumption as degenerate can slide into authoritarianism. The thesis does not prescribe the decider; it prescribes the metric (exergy) and the direction (tax entropy, subsidize capacity). One person’s VR game may be another’s respite; the Entropy Tax tiers by intensity of use, not by moral verdict on the activity.

The Entropy Tax is a planned-economy lever. It challenges laissez-faire by design. The tradeoff is explicit: accept a price on high-entropy consumption or accept that the Hedonist’s demand will continue to crowd out the Architect’s. Implementation risk is in the calibration, not in the principle.

The corrupted demand framework asserts that capitalism’s value-blindness—all dollars look the same—misallocates resources toward ephemeral pleasures and away from projects with lasting societal benefit. Not all demand is created equal; when comfort is king, progress can become a pauper.

In depth: Examples of Capitalism’s Harmful Side-Effects

The “corrupted demand” issue is just one facet of how capitalism can produce harmful outcomes when profit and consumer demand are the only guiding stars. Here are a few concrete ways in which capitalist market dynamics may cause harm or inefficiency:

Short-Term Profit vs. Long-Term Good

Firms often prioritize immediate profits over long-term benefits, which can hurt society. For example, major pharmaceutical companies have been known to spend more on marketing than on research. In 2020 , amid a global health crisis , 7 of the 10 biggest pharma companies shelled out significantly more on sales and marketing (promoting their drug products) than on R&D for new treatments. Pfizer spent $12 billion on marketing vs. $9 billion on R&D, and Johnson & Johnson $22 billion vs. $12 billion, to name a couple. [3] This skew suggests that delivering shareholder value (through aggressive product sales, advertising, and price optimization) outweighed the societal value of investing in new cures. In a profit-driven system, it’s often more lucrative to exploit existing demand (or create demand via ads) than to fund risky innovation , a clear case of misaligned incentives that can harm consumers (e.g. high drug prices, fewer truly novel therapies).

Negative Externalities (Profit Privatized, Costs Socialized)

Capitalism’s track record with environmental and social externalities is notoriously poor. Companies maximize profit by using the cheapest means available, often ignoring costs they can offload to society (unless forced otherwise). A classic example is pollution and climate change: burning fossil fuels has long been hugely profitable for oil companies, while the climate risks were borne by the public. Even when technology exists to move to cleaner energy or more efficient transit, incumbents may resist change to protect profits. A recent lawsuit by the State of Michigan accuses major oil companies (BP, Exxon, Chevron, Shell, etc.) of acting as a cartel to “suppress” clean energy and electric vehicles , essentially colluding to “forestall meaningful competition from renewable energy and maintain their dominance”. [2] The suit alleges that for decades these firms restrained the rollout of EV technology and renewables to keep consumers hooked on oil, resulting in higher energy costs and delayed adoption of green tech. In short, market leaders sometimes find it profitable to create scarcity or delay innovation, even when it harms the public (through pollution or higher long-term costs). It often takes government action (regulation, antitrust, carbon taxes, etc.) to counteract these externality-driven harms, since the free market by itself doesn’t penalize polluters until damage is already done.

Planned Obsolescence and Consumer Waste

Capitalism encourages selling more products, which can lead companies to design products to fail or become outdated faster than necessary. This “planned obsolescence” maximizes repeat sales but at the expense of consumers and the environment. A famous historical case is the Phoebus cartel of the 1920s: leading lightbulb manufacturers secretly agreed to artificially reduce bulb lifespans by over 50% (from 2,500 hours to about 1,000 hours) so that customers would have to buy bulbs more often. They even marketed the new bulbs’ shorter life as if it were improved “efficiency”. [1] In modern times, we see similar patterns in consumer tech , from smartphones that stop getting software updates after a few years, to appliances that are hard to repair. The result is piles of e-waste and extra expense for consumers, purely to pad corporate revenues. As one report put it, planned obsolescence is “intended to maximise corporate profits at the expense of consumers and at great cost to the natural world”. [1] This is a direct harm created by capitalist incentives: longevity and sustainability are often bad for business if a company can lock customers into a cycle of constant repurchasing.

Inequality and Erosion of Social Fabric

A broader (but important) harm often attributed to unconstrained capitalism is extreme inequality. Successful firms and investors can accumulate massive wealth, while workers’ wages stagnate and public goods are under-provisioned. For instance, labor productivity and corporate profits have risen for decades, but median wages have not kept up , a gap sometimes called the 50-year productivity gap (the Liquid Labor site’s “Great Stagnation” refers to this) where gains flow mainly to owners of capital. Extreme inequality can breed social unrest, “deaths of despair,” and a breakdown in social cohesion. This isn’t a single-company example, but rather a systemic outcome: when maximizing return on investment is the sole goal, worker welfare and equality tend to suffer, absent counterbalancing institutions (unions, social safety nets, etc.). While inequality per se is not “corporate malfeasance” in the way pollution is, it’s a byproduct that many argue is harmful , undermining democracy and long-term economic stability. (For example, the top 1% globally have captured a huge share of new wealth in recent years, far more than the bottom half of humanity, illustrating the skew in gains.)

Capitalism’s competitive, profit-driven nature produces incredible innovation and wealth , but it also permits harmful behaviors whenever those behaviors are profitable and not illegal. Whether it’s misallocating resources to trivial uses (“corrupted demand”), dumping costs on the public (pollution, health risks), exploiting consumers’ wallets (planned obsolescence), or neglecting social considerations (inequality), the market by itself has no moral compass. As the saying goes, “the market knows the price of everything and the value of nothing.” These examples underscore why checks and balances (regulation, taxes, public investment, or new economic frameworks) are often proposed to address capitalism’s blind spots.

Do Corporations Stall Technology to Maximize Profit? (Stagnation vs. Innovation)

Do corporations stall technology to maximize profit? The record is mixed: striking cases of willful stalling exist alongside cases where incumbents that resisted innovation were overtaken. The following instances illustrate the former; the Kodak outcome illustrates that suppression can backfire. [4]

Deliberate Suppression

In some cases, firms have actively squashed innovations. One of the most notorious examples is Kodak and the digital camera. [4] Kodak actually invented the first digital camera in 1975, but the company’s leadership killed the project for fear it would cannibalize their hugely profitable film business. As one account describes, Kodak’s management reacted by essentially saying “that’s cute , but don’t tell anyone about it” when shown a digital camera prototype. They focused on short-term film sales and buried a technology that could have kept them industry leaders. Of course, digital photography proliferated anyway (via competitors who seized the opportunity), and Kodak’s suppression backfired , the company’s core film business collapsed and Kodak filed for bankruptcy in 2012. This case is a classic innovator’s dilemma: a dominant player had the tech in hand, but because it threatened their legacy profits, they slowed or stopped its development, ultimately to their own detriment.

Collusion and Cartels

Beyond individual firms, sometimes entire industries collude to slow innovation. The earlier example of the Phoebus lightbulb cartel fits here too , multiple companies agreed not to make longer-lasting bulbs, effectively reversing technological progress in bulb lifespan to boost sales. [1] More recently, as mentioned, fossil fuel companies have been accused of coordinating to delay the adoption of renewables and electric cars. If the allegations are true, these oil giants essentially acted to stall energy innovation to maximize decades’ worth of oil profits. Such behavior is usually done in the shadows (since overt collusion is illegal), but the economic motive is clear: when a new technology (like EVs) could upend a lucrative market (oil and gas), incumbents have incentive to throw sand in the gears , via lobbying, patent control, buying up and shelving new tech, or creating market obstacles , until they can either control it or until they’re forced to change.

Incrementalism Over Breakthroughs

Even without conspiracies, large firms can slow-play innovation by focusing on incremental upgrades rather than big leaps. Think of how smartphone makers release new models each year with just slight improvements , some critics argue they could introduce more durable batteries or radical features sooner, but doing so might shorten the profitable cycle of people buying a new phone every 1,2 years. This isn’t outright “suppressing” a known technology, but it is a kind of paced innovation for profit. The product strategy is to milk each generation thoroughly rather than jump to the end-state. Similarly, auto manufacturers historically were accused of being slow to improve fuel efficiency or safety until regulations demanded it, preferring to sell gas-guzzlers and spare themselves R&D costs. In these ways, the market can stagnate not because the tech is unavailable, but because the business case for rapid change isn’t compelling without competition or regulation.

Counterpoint , Competition Spurs Innovation

On the other hand, capitalism also has the self-correcting mechanism of creative destruction. If one company drags its feet, a hungry competitor (or upstart) can leap ahead. The Kodak story above illustrates this: [4] Kodak stalled digital tech to protect film, but rivals like Canon, Sony, and later smartphone makers pushed digital cameras forward and ate Kodak’s lunch. In the long run, it’s hard to completely bottle up a transformative invention , eventually someone will commercialize it. Companies that try to freeze the status quo too long may end up disrupted themselves (as seen with many once-dominant firms that failed to adapt). In sectors with strong competition, the pressure to innovate is relentless , for instance, no single computer manufacturer could halt the personal computing revolution, and no telecom giant could stop the internet or smartphones once competition kicked in. Thus, while monopolistic or collusive behavior can stall progress for a time, it’s often unsustainable in the face of market forces and technological inevitability.

Why Robotic Money is Needed (Machine Economies)

As we move into an era of AI and automation, there’s growing recognition that machines will increasingly be economic actors in their own right – and our legacy financial system isn’t built for them. [9] Robots and AI agents don’t have bank accounts or social security numbers, and they operate at speeds and scales that human payment systems can’t match. This is why many futurists (and the Liquid Labor research) argue that we need a form of “robotic money” or machine-native currency for the coming machine economy.

Consider a simple scenario: an electric delivery drone needs to autonomously recharge itself at a station. How can it pay for the electricity? It can’t exactly swipe a Visa card or log into a Bank of America account – those systems assume a human identity and operate relatively slowly, with fraud checks, business hours, etc. As the Liquid Labor essay points out, “robots do not have bank accounts. They cannot pass KYC checks at JPMorgan.” An autonomous system can’t furnish a passport or answer security questions about its mother’s maiden name! Thus, if we expect robots to engage in commerce (buying power, data, services from each other), we need trustless, automated payment networks that machines can use 24/7 without human intermediation.

Cryptocurrencies, especially Bitcoin and its offshoot technologies, present a compelling solution here. Bitcoin operates on a decentralized network, open to anyone (or anything) with an internet connection – no need for a bank’s permission or a government-issued ID. It settles transactions quickly (especially with layer-2 solutions like the Lightning Network for instant micropayments) and irreversibly. For a machine, the advantages are clear: a robot can hold bitcoin (or a digital token) in a software wallet and transmit it to another machine programmatically in exchange for resources, all in seconds and with cryptographic security. There’s no risk of a payment being arbitrarily reversed or an account frozen, since Bitcoin’s rules are enforced by code and consensus, not by trusting a third party. In short, crypto can be “native money for machines.”

We explicitly frames Bitcoin as the “Bridge Protocol” to an energy-based, automated economy. [8] Why? Because Bitcoin, through its Proof-of-Work mining, is effectively “tied to physics”. To mint new bitcoins, miners must expend real energy and computational work – this makes each coin like a “battery of value” representing a chunk of expended energy. In a future where economic output is driven by robots (which run on energy), it makes intuitive sense to use a currency that itself is linked to energy expenditure. Unlike fiat money, you “cannot print Joules” out of thin air. Bitcoin’s supply is capped and its issuance is governed by thermodynamic cost, so it can serve as a neutral yardstick in a machine economy that might otherwise tend toward abundance and deflation. Moreover, Bitcoin enables microtransactions and machine-to-machine (M2M) payments: imagine an AI service charging you 0.0001 BTC per second of computation it provides, or two devices negotiating a few satoshis (fractions of BTC) for an API call. This is already being tested with the Lightning Network, where payments can be as small as a single satoshi and can stream continuously. Traditional banking cannot handle millions of tiny transactions between autonomous agents, but crypto networks potentially can. [5] [10]

References

- [1] Population Matters – “From lightbulbs to smartphones: the practice of Planned Obsolescence”

- [2] InsideEVs – “Michigan Is Suing Oil Companies For ‘Suppressing’ EVs” (Jan 2025)

- [3] CSRxP (Council for Affordable Health Coverage) – “Big Pharma Spent More on Marketing than R&D During Pandemic” (Oct 2021)

- [4] World Economic Forum – “Kodak invented the digital camera – then killed it.” (David Gann, 2016)

- [5] NDTV – “Moltbook Chaos Fuels 7,000% Surge In AI-Linked Memecoin” (Jan 31, 2026)

- [6] Glassnode Research – “Bitcoin Ownership is not Highly Concentrated – But Whales are Accumulating.” (Feb 2021)

- [7] River Financial – “Who Owns the Most Bitcoin in 2026?” (Dec 2025)

- [8] Citrine Capital Advisors – “AI and Bitcoin: How the AI Boom Is Strengthening Bitcoin.” (Aug 2023)

- [9] Yahoo Finance – “Why stablecoins could power the AI agent economy” (quoting Circle CEO Jeremy Allaire, 2023)

- [10] Bloomberg Opinion (Matt Levine) – “AI Can Steal Crypto Now” (Dec 2025) (see also Asher Law’s summary on AI rewriting crypto theft)